CPRE Reports Ethical Competency Shortfalls for PR Grads / New Pros

The Commission on Public Relations Education (CPRE) report, “Navigating Change: Recommendations for Advancing Undergraduate Public Relations Education – the 50th Anniversary Report” was published recently, edited by esteemed academicians Elizabeth L. Toth of the University of Maryville, College Park and Pamela G. Bourland-Davis of Georgia Southern University.

Kudos to all CPRE-affiliated academicians whose work and leadership contributions are cited in this valuable report.

As a board member of a CPRE-member association, ICCO, I appreciate the diligent work presented in the CPRE’s report.

In particular, I’ve made note of the report’s treatment of how public relations ethics is dealt with as a subject in university-level PR classrooms.

The word “ethics” or similar forms of that word appear more than 350 times in the CPRE’s report.

That’s a lot, and it reflects strong topical coverage and substantive depth. In fact, the editors dedicated an entire chapter to the subject, in “Chapter 6: Ethics: An Essential Competency, but Neglected”:

I’m beyond pleased that ethics received this kind of focus in the report.

It’s heartening to see a much-needed academic PR topic, boldly reported – particularly when there is obvious cause for concern, as the CPRE report documents.

#PRethics is indeed critically essential but all-to-often neglected badly.

Such has been my message for decades.

All too often, though, the message urging that we fix this neglect seems to have fallen on deaf ears. I have to admit that, at times, I feel like a lone megaphone in the PR Wilderness.

As “essential” as ethics competency indeed is in PR, just who or what is doing the “neglecting,” as the CPRE’s report clearly states?

Only by addressing where the neglect is coming from can we fix this problem.

The CPRE Ethics Team opened Chapter 6 of the Report, writing in part (my bold type added, for emphasis):

“As new and continuing ethical challenges emerge and linger in our industry around areas of artificial intelligence, data privacy and misinformation, survey results indicate our newest professionals are not adequately prepared.”

The Executive Summary of the report boiled down these top-line findings (my bold type added, for emphasis):

“Practitioners were especially critical of young professionals’ lack of mastery of essential ethics skills in their first five years, especially their lack of ethics skills in critical thinking, strategic planning, and a personal code of ethics. A top priority for future educational efforts should be to develop ethical critical thinking skills. Also, new professionals reported experiencing hostile workplace environments/harassment more than anticipated.”

That last sentence is quite the kicker, in my view.

I again must ask… Whose fault is that?

This isn’t a finger-pointing directive. It’s a legitimate question for the full industry to ponder and, hopefully, to reconcile.

For starters, let’s consider the grand irony that while New Professionals need ethical competencies, this specific early-career cohort of practitioners also report having experienced “hostile workplace environments/harassment.”

Now consider this universal truth:

Hostile Workplaces + Speaking Up = Career-Damaging Retaliation

Just as in any organization, this equation holds true in any PR firm, any corporate or organizational PR department, and certainly (I can attest to this one) any PR member association.

This irrefutable equation reflects the PR industry’s rather conflicted – if not overtly troubled and highly uncomfortable – relationship with the notion of any PR practitioner or educator speaking up against observed misconduct from within the ranks of organizations where said misconduct is occurring.

Think about misconduct, in general.

And now, think about “good PR”’s relationship with evidence of provable misconduct.

Oil-and-water doesn’t even begin to describe it. The two don’t cohabitate well.

PR’s reputational problem as an industry is that too many people in our sector have made a long, well-compensated living out of insulting the public’s intelligence through organizational gaslighting, masquerading as “PR.”

The emperor can parade around without any clothes, but as long as certain PR weavers still get to collect their paychecks through creative wordsmithing and artful changing-of-the-subject, all is deemed well.

PR practitioners of integrity know that gaslighting is wrong, just as herd-mentalities of go-along-to-get-along can be highly unethical, too. Yet these scenarios are quite common in PR.

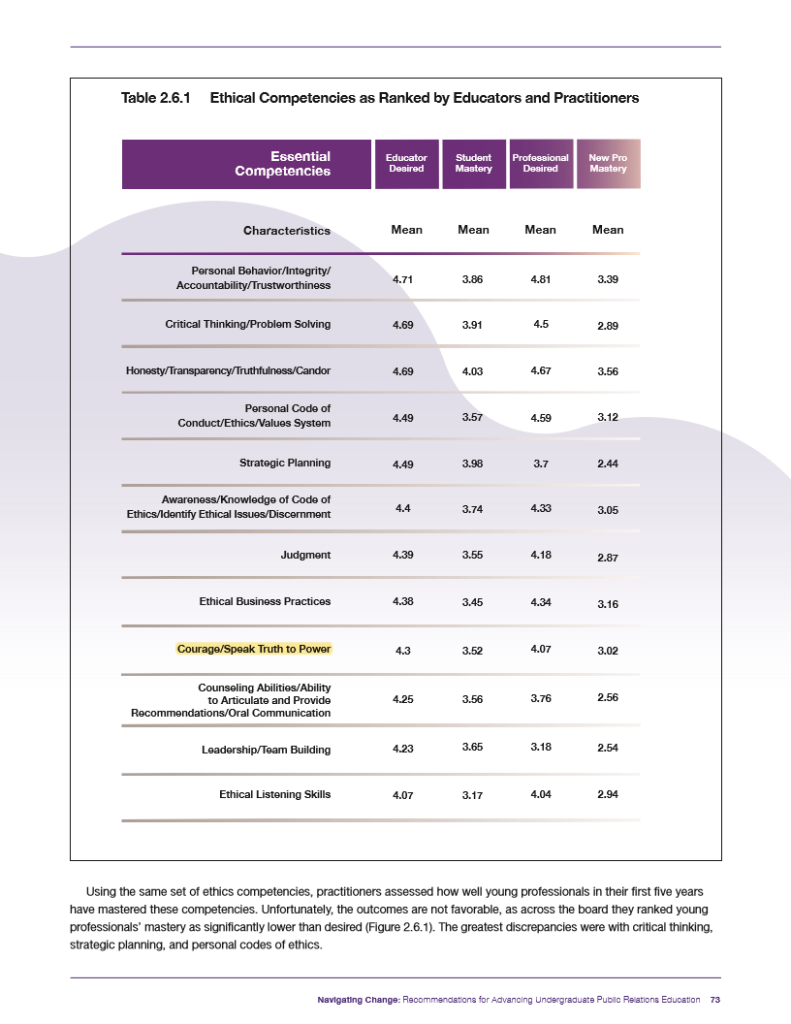

Interestingly, in the CPRE’s Chapter 6 rank-order listing of “Essential Ethical Competencies,” “Courage / Speak Truth to Power” ranks No. 9 – Ninth! – on a list of 12 ethics competencies, as judged by “Educator Demand.”

It ranks only slightly higher by “Professional Demand”:

Why on earth “Courage / Speak Truth to Power” isn’t in the Top 3 “Essential Ethical Competencies” is beyond me. (This ranking isn’t the CPRE Ethics Team’s fault, as they’re simply the messenger of the data here.)

After all, one can possess within oneself all the “Personal Behavior / Integrity / Accountability / Trustworthiness” in the world (which was ranked No. 1), but what good is it if Rome is burning all around you due to obvious misconduct by those who purposely lit the fuse for purposes of self-gain, but you’re too intimidated and threatened to speak up?

To me, that’s the $64,000 question, most worthy of study, in the category of skills we need to equip PR students toward wielding some form of command.

It’s also essential to study this question through the lens of typical retaliatory whistleblower experiences and journeys. You simply cannot have valid academic treatment of “speak up” organizational dynamics without treating the whistleblower element.

Interestingly, the word “whistleblower” or “whistleblowing” is mentioned only once in the CPRE’s report.

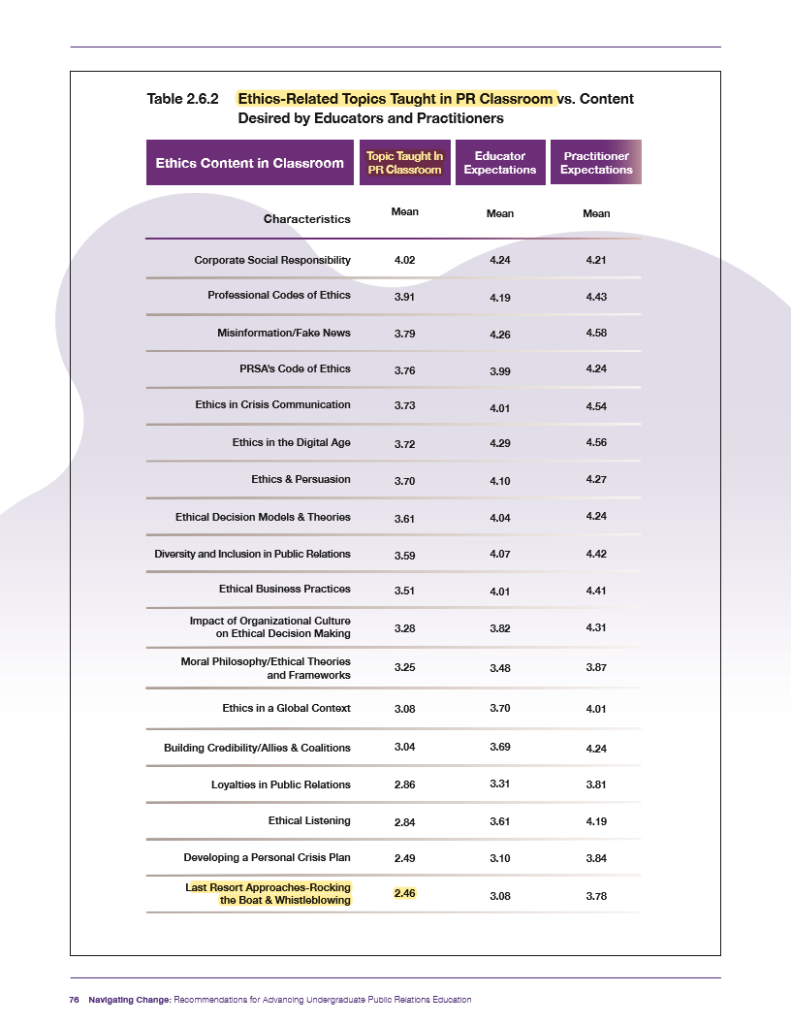

It ranked dead-last among “Ethics-Related Topics Taught in PR Classrooms” (again, no fault of the CPRE Ethics Team, as they’re simply reporting the data):

So, there again: bitter irony!…

We are expecting “New Professionals” to exhibit robust ethical competencies including speaking up in their organizations.

Meanwhile, New Pros are telling us directly that they’re dealing with hostile workplaces and even harassment, and yet we’re not equipping them to any adequate extent whatsoever with how to report misconduct without also facing even more hostility and harassment than they’re already dealing with.

It may be the vast majority of our leaders in the industry who are the ones needing to brush-up on their speak-up skills – not our industry’s entry-level folks with the least amount of power in any organization and who are most at-risk of being chided / “dressed-down,” disciplined, demoted, or even eliminated from the workplace (or from, say, a PRSA membership roster) for reporting facts not to management’s liking.

In many organizations, there doesn’t even exist a fair, unbiased, and ethical mechanism for reporting misconduct.

In CPRE-member association PRSA, for example, the organization didn’t have a “grievance procedure” for some 70 years of its existence, until such a slew of complaints were registered from 2017-18 that the PRSA Board essentially was forced to create one.

But then, they created one that’s inherently unethical by allowing leadership members at the center of an ethics complaint to adjudicate — or appoint close cronies to adjudicate (or summarily dismiss) — any complaint about incidents that they themselves may have created. When PRSA is in a real ethical or legal jam, they hire an attorney — paid for with member dollars — to interject themselves into the process and overrule any protest of PRSA leadership’s own conflicts of interest.

Sound “ethical”?

Sound like a modality that students need to be taught as an example of ethical governance?

I think not.

When we expect PR practitioners at any level (entry, mid-, senior, or executive-level) to “speak truth to power” about misconduct that’s occurring, then we are expecting them to shake a veritable hornet’s nest… but with no protective gear for themselves.

And that’s significant, because while only one hornet’s sting can certainly hurt, enough of them attacking their human target at once can kill. Not to sound overly-dramatic, but emotional abuse in some workplaces is a serious reality, and it can have serious consequences.

A 2023 survey from the American Psychological Association “revealed that 19% of workers say their workplace is very or somewhat toxic, and those who reported a toxic workplace were more than three times as likely to have said they have experienced harm to their mental health at work than those who report a healthy workplace.”

Dealing with workplace or other organizational retaliation is very much like being stung.

It can happen from out of nowhere, when you least expect it, even from people whom you always considered to be good colleagues, or even friends.

Having your career “killed” or your standing harmed within a community of colleagues from repeated stings of retaliation is the worst-case scenario, in every metaphorical sense of emotional abuse and threats to workplace mental wellness. There are volumes of studies backing this up… that toxic organizational cultures breed this very type of threat to people.

So why, then, do our PR industry ethics codes provide no protective gear from the hornet nests of whistleblower retaliation against people trying to speak up for ethics, in good faith?

Is it because those who “own” the codes refuse to update them, with language that forbids improperly retaliatory management behaviors against employees or members with less power?

If I’m still asking this same question a year from now because no substantive change has resulted in PR ethics codes, then I’m quite rightfully going to presume a “Yes!” as the answer to my own question, as to the refusal motive.

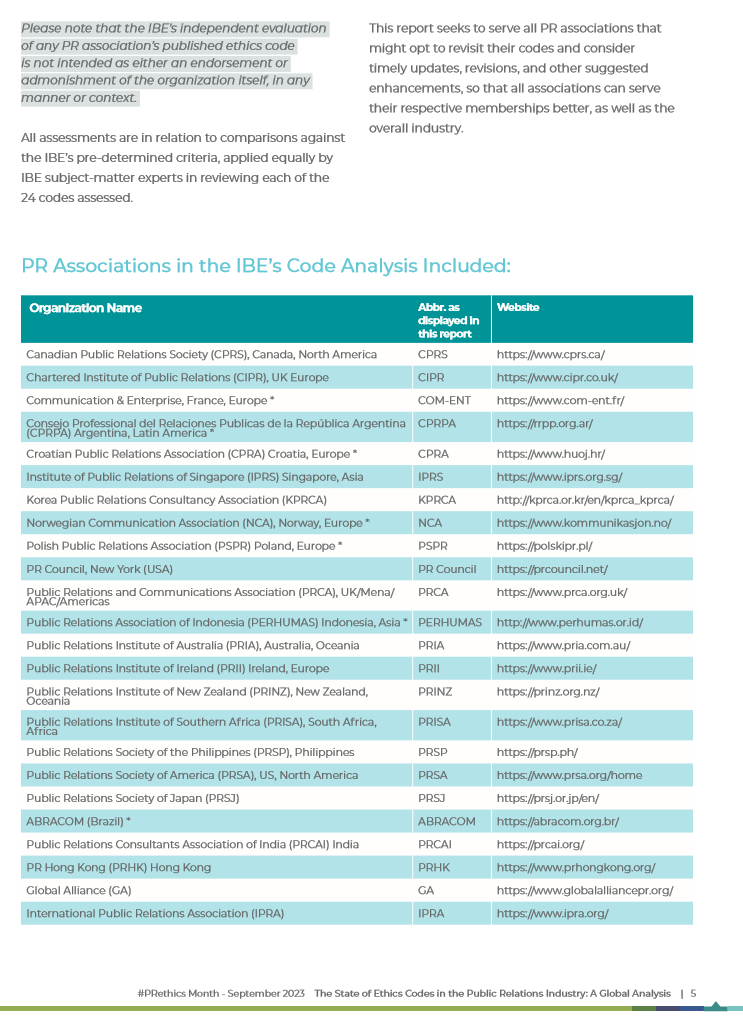

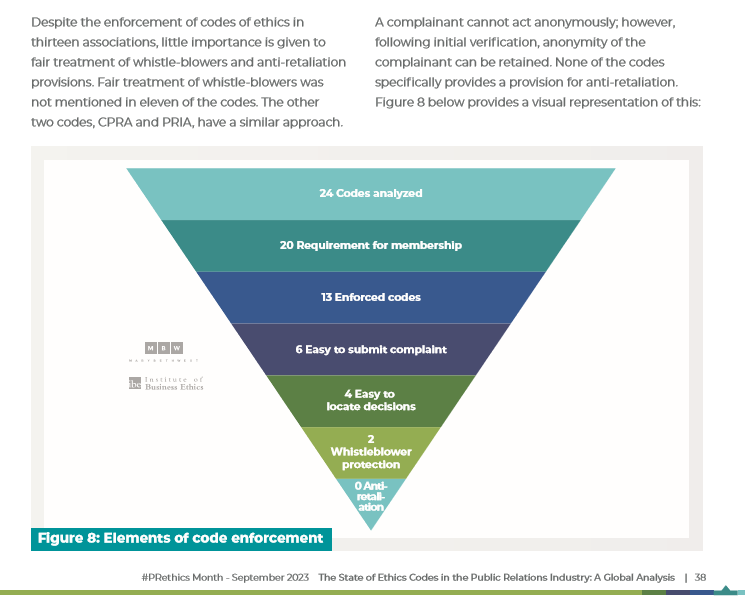

My white paper published last year of 24 PR industry ethics codes worldwide documented that only two codes offered any sort of whistleblower-protection mention, and none – ZERO – espoused any virtue of anti-retaliation to support properly those in PR with the courage to “speak up.”

This overt degree of ethics codes’ omission of whistleblower-protection and anti-retaliation provisions is a big deal, particularly if the idea of “speaking up” as an ethical value is anywhere on the PR industry or PR-education table, as it indeed is in the CPRE report (a fact that I appreciate!).

While so many ethics codes exist in the global industry and CPRE member organizations like the PR Council have their own ethics codes worthy of consideration, the CPRE tends to give outsized attention to the PRSA Code of Ethics alone as a source-document on ethical teaching for students.

For all the attention given to the PRSA Code of Ethics as a standard-bearer, it also should be acknowledged that this document is some 25 years old, hasn’t been updated even once since the dawn of social media, and rests on PRSA’s laurels with no treatment nor any mention of anti-retaliation being important.

Actions speak louder than words, and silence can be deafening.

Even though the entire purpose of exposing misconduct is to force misconduct to cease-and-desist so that the organization can return to an authenticity of acceptable practices worthy of public trust, far too many PR practitioners cannot – or, rather, will not – make that intellectually reasoned step of short-term pain (exposing misconduct to force it to cease) for long-term gain (a healthier ethical core of compliance).

Who controls the power dynamics of such situations?…

Leaders!… from departmental managers to organizational c-suites and boardrooms.

Not students or new professionals, who might justifiably feel the bite of misplaced criticism from the CPRE’s report in stating that PR practitioners or hiring managers don’t think New Pros know much of what they should on the ethics front.

Should students and new professionals be educated and sophisticated about these issues and dynamics? Most assuredly, Yes! (And kudos the CPRE’s Ethics Chapter Team for making that case.)

However, with that said, is this core problem of organizational misconduct an issue that students and new professionals have any control over – or likely will have any control during the first half-decade or so of their careers, given the silencing effect of whistleblower retaliation? Overwhelmingly, No.

I urge the CPRE to consider turning right-side-up this urgency of #PRethics education, because it’s currently upside-down, though by no direct fault of the CPRE’s educators.

Senior-leaderships are essentially getting a free-pass on their own ethical competency assessments, even though it is they who hold the keys to that kingdom.

Let’s face it: We all know some PR industry “leaders” who insist on being dumbfoundingly challenged when it comes to making an ethical choice, even if armed with every PR ethics code in the world… not that such folks are inclined ever to consult one!

I appreciate and respect the reporting of the CPRE’s Ethics Chapter Team specific to the valid and hugely insightful data reflected in Chapter 6, which includes several charts quantitatively ranking ethical competencies from educator and practitioner standpoints.

Without question, it’s valuable information.

By raising the issues I’m raising here, I strongly urge a reconsideration of just who educators are being asked to educate on this matter of ethics.

Yes, they’re paid to educate students paying tuitions at their colleges and universities.

But are the CPRE’s “Organizational Members” – and there are a bunch of us – providing much-needed pathways for PR’s academic community to educate their own members… including their most senior members, with the most power to run ethical organizations fully allowing speak-up cultures and non-retaliation?

Admittedly, my bias is that I’ve been a long-time whistleblower of observed misconduct in the PR industry for many years (by one association in particular) and have experienced voluminous waves of unfair, unjustified, and even illegal retaliation running afoul of state law, as a result.

With that said, the fact that I possess this bias doesn’t mean I’m wrong. I’m posting this blog now, in a spirit of open debate.

Whistleblower-protection requires that anti-retaliation must be written into PR codes of ethics.

Further, these codes shouldn’t simply be taught in PR classrooms to career entrants with the least amount of power in the foreseeable future. Instead, codes should be reinforced and promoted as an industrywide voice for change among the highest ranks of leadership in PR, starting with the PR member associations that steward industry codes.

Which brings me to my final point pertaining to PR students and the CPRE’s coverage of supportive industry pathways to help students develop and grow.

Anyone who has followed my national and international advocacy work for any length of time well-knows that I first began registering serious concerns of U.S. domestic industry-association misconduct problems in 2017 – the very year I was inducted into the PRSA College of Fellows.

This particular association has now managed to lose nearly 50% of its student-society membership over the course of the past decade.

In 2014, the student association of PRSSA stood at some 11,500 members:

The parent association’s most recent (December 2023) reporting of student membership has now dwindled to less than 5,800:

These stunning U.S. membership losses are not mentioned in the CPRE’s report.

In fact, the CPRE report only mentions “PRSSA” nine times in 118 pages, mostly concentrated on Page 29, in relation to the sub-topic, “Networking and Experiential Learning Opportunities.”

Sadly, the student society national membership is now hovering around the same level it was when I was a student myself, serving as national public relations director of PRSSA, some 30 years ago.

By the numbers, it seems students have voted with their feet as to their faith or belief in the parent organization’s values or at least its ability to deliver value itself, however it is that the students themselves define it, as is their right.

Either way, maybe PR students know something that the industry either doesn’t know or simply has opted to “look the other way” by choosing to ignore.

Notably, looking the other way is not listed anywhere in the CPRE report as an “ethical competency”… because, of course, it isn’t one.

I invite the public relations academic community to review my white paper, published in September 2023, with original research of 24 PR industry ethics codes assessed independently by the London-based Institute of Business Ethics.

I also invite the academic community to download its own member association — ICCO’s — most recent World Report, which includes data tied to ethical perceptions in the global industry that likely should factor into future CPRE reports.

I recommend that since CPRE includes some 70 (!) board members, and with member organizations well-outside the United States, that more universal study and assessment of PR education issues and needs external to the U.S. or North America be included in future reports. After all, we are a global industry in a widely interconnected global society, and so we need this broader view.

Again, many thanks to those who produced this most recent CPRE report!

###

Check out the February 2024 PRmoment podcast, airing from the United Kingdom, featuring Mary Beth West and Trevor Morris — both Fellows of the PRCA — in their discussion of PR ethics codes, hosted by Ben Smith, FPRCA: